In Part 1 of this series, we explored core architecture patterns for incorporating domain knowledge (comparing RAG, fine-tuning, and hybrid approaches). In Part 2, we focused on the model layer and the choice between closed-source, open-source, or local models. Now in Part 3, we turn to the Data & Retrieval Layer – the foundation that feeds your models with the right information. This layer determines whether your AI’s answers are grounded in truth or riddled with hallucinations. We’ll explain how to design, implement, and operate a robust data and retrieval pipeline that: maximizes answer quality, minimizes hallucinations, controls cost/latency, and meets privacy compliance. We’ll stay practical and vendor-agnostic, comparing popular tools and frameworks. Let’s dive in.

1.Why the Data & Retrieval Layer Decides Real-World AI Quality

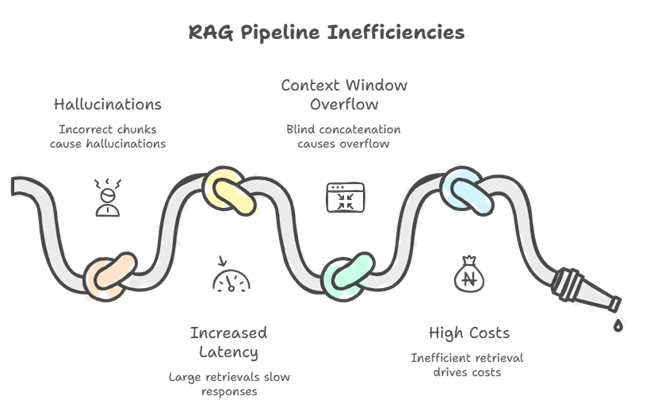

Even the most advanced LLM will falter if it’s fed bad or missing data. In real-world AI systems, the retrieval layer often makes the difference between an accurate, trustworthy answer and a misleading hallucination. Studies and industry experience show that generation quality is fundamentally a retrieval problem – if your pipeline fails to fetch the right context, the model’s output “collapses” in quality, no matter how good the model is.

Conversely, a well-designed retrieval layer can dramatically boost factual accuracy and reduce nonsense: for example, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) supplies the model with verified reference text, so the LLM doesn’t have to improvise an answer from thin air. OpenAI noted that RAG “can significantly reduce hallucinations” by grounding the model in actual source documents.

Answer quality. The retrieval layer directly controls what information the model sees. If relevant facts are missing from the retrieved context (or drowned out by irrelevant text), the model may guess or fill gaps with incorrect content. Many early failures of QA chatbots trace back to retrieval retrieving semantically similar but wrong passages. For instance, a query about “2023 tax law changes” might wrongly bring up a 2022 tax document that uses similar wording – leading the model to give outdated info. A robust data layer mitigates this by using precise search and filtering to find the truly relevant snippets, and by applying re-ranking to push the best answer sources to the top. As a result, the model can cite the actual text in its response, increasing correctness and enabling verifiable answers. In fact, business leaders often require that AI responses include source citations precisely because it proves the retrieval step worked (the AI is saying “according to document X, ...” instead of hallucinating).

Latency and cost. The architecture of your retrieval pipeline affects performance and expenses. Retrieving 50 irrelevant chunks wastes computing power on the vector search and bloats the prompt fed into the model, increasing token counts and latency. A disciplined approach - such as filtering by metadata first and then retrieving a small number of high-quality matches - keeps the prompt lean and speeds up generation. Without careful design, naive RAG prototypes commonly slow down over time as the knowledge base grows. Every query scans too much data or returns too many results, leading to long tail latencies. Optimizing the data layer with proper indexes, sharding strategies, and caching is crucial to maintaining low query latency as you scale to millions of documents. This, in turn, controls cloud inference costs because smaller context means cheaper LLM API calls. In short, the retrieval layer balances relevance, speed, and cost. While a high-quality result may require an additional reranking step, which uses slightly more computing power, it's worth it if it prevents a hallucination or avoids a costly 16k-token prompt.

Continuous improvement. Unlike static model weights, you can iterate your data layer daily. New or corrected information can be indexed and begin influencing answers immediately without the need for retraining. This agility is vital for real-world deployments where facts change, such as policies and knowledge base articles. It also means that the responsibility for ensuring the quality of your AI shifts heavily to your data engineering practices, such as keeping the knowledge base fresh, ensuring data correctness, and monitoring retrieval efficacy. In production, teams often find that improving the ingestion and retrieval pipeline is more beneficial than adjusting model prompts. As one engineer put it, building a RAG system is easy, but “building RAG that works in production is not” – it requires solid engineering of the data layer. All these reasons are why we say the retrieval layer “decides” real-world AI quality.

Finally, compliance and trust depend on the data layer. This is where you determine what information the AI is permitted to access and share. For instance, if certain documents are confidential or region-restricted, the retrieval layer must filter them out in response to unauthorized queries. RAG enables fine-grained control - the data remains in a secure database, and you can ensure that the system only retrieves documents that the user is authorized to view. This level of access control would be impossible if all knowledge were embedded in model weights. We'll discuss governance in more detail in Section 6, but the key point is that careful retrieval design boosts accuracy and prevents the accidental leakage of private data, thereby building user trust. In summary, an AI’s intelligence is only as good as its data infrastructure. Next, we’ll examine how to choose the right "pipes" - starting with vector databases.

2. Vector Databases: How to Choose for RAG and Beyond

Vector databases are the workhorses of retrieval-augmented AI. They store embeddings (numerical vectors) of your texts and rapidly retrieve the closest matches for a given query vector – enabling semantic search that finds relevant information even when keywords don’t match exactly. A myriad of vector DBs have emerged, but they differ in index algorithms, hybrid search capabilities, filtering, scaling, and ecosystem. The table below compares five popular options for RAG use cases (all support common distance metrics like cosine or Euclidean):

Vector Database Comparison

Key takeaways: If you need an out-of-the-box managed solution and can budget for it, Pinecone offers ease of use and auto-scaling (popular for startups that want quick deployment). But Pinecone’s closed nature means less flexibility – e.g. you can’t self-host it later or modify internals. Open-source options like Weaviate or Qdrant give you more control and can be run on-premises, which is often essential for data privacy. They also now offer managed services (Weaviate Cloud, Qdrant Cloud) that are competitively priced (Qdrant even has a forever-free tier). Milvus is a strong choice if you have truly massive scale or need exotic index types (IVF, DiskANN) to fine-tune performance/cost – for example, an Image search over a billion embeddings might benefit from DiskANN on Milvus. However, Milvus currently lacks built-in hybrid search; you’d pair it with Elasticsearch or use a separate step to handle keywords. Weaviate and Qdrant, on the other hand, are “AI-native” databases with full-text + vector hybrid search baked in, which is great for question-answering on enterprise text (often you want to boost exact matches of a term in addition to semantic similarity). Both also support multi-tenancy and granular role-based access in their enterprise versions – relevant if you need to segregate data by user or client.

Finally, pgvector is unique: it brings vectors to an SQL database. This is attractive if you want to keep all data in one system (for example, augmenting a product catalog Postgres DB with vector embeddings for semantic search). It’s best for smaller-scale cases or where tight integration with relational data is a priority. The trade-off is performance at scale – Postgres wasn’t built for high-dimensional indexing, so expect to tune parameters (like ef_search for HNSW) and possibly use approximate search for >1M records. In summary, there’s no one “best” vector store – each has trade-offs. Choose based on: data size, query patterns, hybrid search needs, budget, and deployment constraints (cloud vs on-prem).

Next, we’ll look at how to connect these vector stores with your actual document data and build a retrieval pipeline that goes beyond “nearest neighbors” to deliver relevant, up-to-date, and safe results.

3. Document Stores & Retrieval Plumbing

A common misconception is that a vector database alone constitutes your “knowledge base.” In reality, a production-grade system will also include a document store (or data lake) holding the source documents and a lot of “plumbing” to connect pieces together. The vector DB typically stores embeddings and some metadata, but it might not store the full original text (embedding indices are optimized for similarity search, not for long text storage). Therefore, you’ll often maintain a document repository – e.g. an object storage bucket or a database – for the authoritative content. The retrieval pipeline will fetch snippets or document IDs from the vector search, then lookup the full text from the doc store when needed (for instance, to show the user the paragraph from a PDF that the answer came from).

Document store choices. Many architectures use cloud object storage (S3, GCS, etc.) or a database (SQL or NoSQL) to hold the raw documents, images, or other data that were embedded. For example, you might store PDFs in an S3 bucket and also keep a preprocessed text version in a SQL table or Delta Lake (more on Lakehouse in section 5). The vector DB would store just an ID and embedding (plus metadata) for each chunk or document. At query time, once you get nearest neighbor IDs, you pull the actual content via the ID from the document store.

This separation is useful for compliance and auditing: you can version your source data, run checks on it, and easily re-process or re-index if embeddings need to be updated. It also means you’re not tying yourself to one vector DB – the raw data is kept in a standard format outside. Many RAG pipelines implement a “dual store” approach: a fast vector index for retrieval and a durable store for the source data.

Retrieval pipeline flow. Let’s walk through a typical retrieval process in a production system:

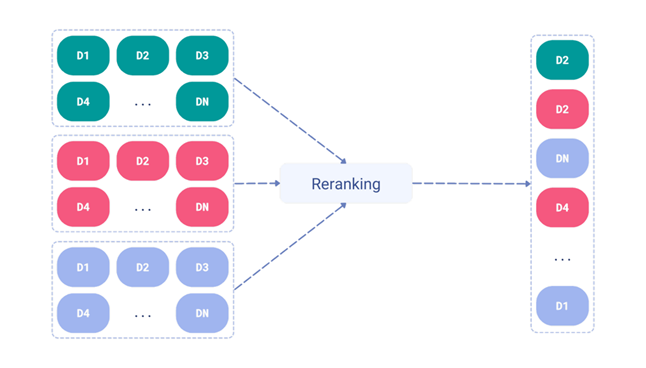

When a query comes in, the system first applies any filters or keyword search to narrow down the candidate set (for example, limit to documents of a certain type or containing key terms). Next, a vector similarity search is performed on the filtered subset, retrieving the top K embeddings (chunks) most relevant to the query. These top candidates are then passed through a re-ranking stage – e.g. a more precise model (such as a cross-encoder or a lightweight language model) reorders them based on actual relevance to the query, boosting precision. After re-ranking, the system can enforce guardrails: filtering out any disallowed content, removing duplicates, and ensuring the final context size fits the model’s input limit. Finally, the relevant text chunks (now curated) are injected into the LLM prompt for answer generation. The LLM uses this retrieved context plus the user’s query to produce a grounded answer.

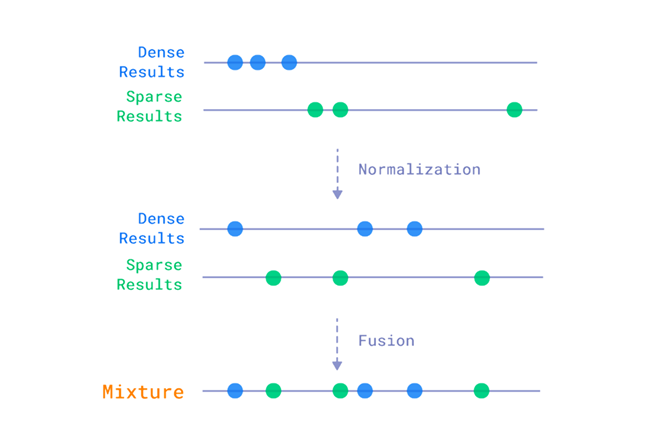

In practice, some of these steps may be optional or combined. For instance, if your vector DB supports hybrid search, the keyword filter and vector recall might happen in onestep (as with Weaviate’s BM25+vector search or Pinecone’s sparse-dense index). Or you might choose not to use a re-ranker for simplicity, instead relying on the vector similarity scores. However, at scale most teams find a multi-stage pipeline yields the best results: “Top-K similarity search is only the first stage. Production systems require hybrid search, re-ranking, and filtering to balance relevance, latency, and context-window constraints.” In other words, a sequence of coarse-to-fine retrieval gives a good mix of recall and precision.

Plumbing considerations: Building this pipeline requires integrating several components. You’ll need a way to orchestrate calls between (a) the vector database, (b) potentially a search engine or database for keyword filtering, (c) a re-ranking model (which could be a hosted model API or a local model), and (d) the language model for final answer generation. In a cloud setting, this often means using a combination of API calls and middleware. For example, your application server might, upon receiving a user query REST call, first query an Elasticsearch for keywords, use the result to query Pinecone for vectors with a filter, then call an LLM API with the retrieved text. Tools like LangChain or LlamaIndex have abstractions to chain these steps, but many teams implement custom retrieval logic for flexibility. If latency is critical, you may co-locate components (e.g. run the vector DB and reranker in the same region or VPC). Some vector DBs (Qdrant, Weaviate) are evolving to handle more of the pipeline internally – for instance, Qdrant’s new Query API lets you do a vector search and a filter and an RRF fusion in one request on the server side.

Document context assembly: Once you have the top-N chunks, how do you present them to the model? A common approach is simple concatenation (joining snippets with separators and maybe a citation tag). But you might also group chunks by source or do a light summarization if you have too many. The retrieval pipeline can include logic to post-process retrieved text – e.g. drop very short or low-relevance chunks, or merge contiguous chunks from the same document into one larger piece. The goal is to feed the model a coherent, de-duplicated context that maximizes the chance of a correct answer. If your chunks have metadata like document title or section headings, you can prepend those to give the model more signal (for example: “Document: HR Policy 2023, Section 5.2: <chunk text>”).

In summary, the retrieval plumbing connects data to the model. It involves multiple components orchestrated in sequence, with careful attention to filtering and re-ranking. Next, we discuss three critical techniques to make this pipeline effective: smart chunking of documents, leveraging metadata, and deploying re-ranking models.

4. Chunking, Metadata, and Re-Ranking That Actually Work

Not all retrieval is created equal – how you chunk your data and rank your results can make or break your system’s quality. Let’s break down best practices for chunking, metadata use, and re-ranking that have proven to work in real-world deployments.

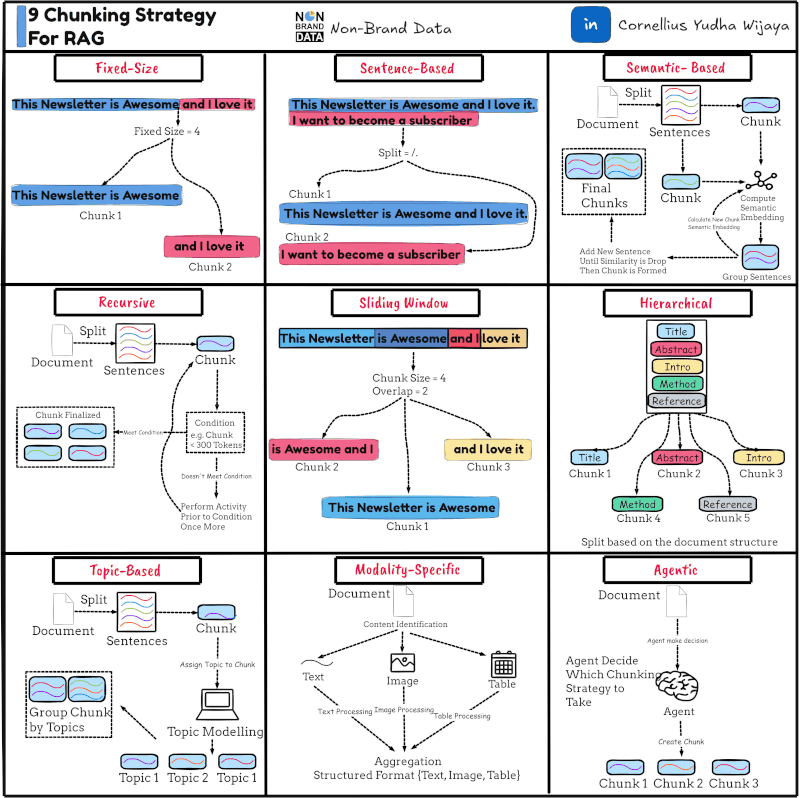

Intelligent chunking: In training demos, we often see documents split into fixed-size chunks (e.g. 500 tokens) blindly. This “naïve chunking” can seriously undermine retrieval. Important context gets split apart – “clauses are separated from their conditions, tables are broken into fragments, headers lose their associated content” – so the model later sees an incomplete piece and might misinterpret it. Instead, chunk along logical boundaries in the document. Preserve semantic units: a paragraph and its heading, an entire FAQ pair, a code function, a table row along with its columns, etc. Yes, we still need chunks to fit the model’s context window (and for efficient embedding), but the strategy is not one-size-fits-all. Treat chunking as “a retrieval optimization problem”, not a trivial preprocessing step. In practice, this means experimenting: you might use shorter chunks (e.g. 100 tokens) with overlap for narrative text where any sentence could be relevant, but use larger chunks for structured documents like manuals (so that an entire section’s info stays together). Some teams use dynamic chunking, where they parse the document structure (via HTML/XML or PDF layout) and create chunks that correspond to semantic sections, only breaking them further if they exceed, say, 256 tokens. The bottom line is to preserve context within each chunk as much as possible. As one guide noted, “fixed token windows [alone] fail to preserve semantic boundaries”, so chunking needs to respect structure while enforcing length limits. If you get chunking right, retrieval wins become much easier – no fancy algorithm will save you if your chunks are garbage.

Check out a related article:

AI in Medicine: Opportunities, Challenges, and What’s Next

Metadata enrichment: Every chunk or document should carry metadata – labels or attributes that provide context and enable filtering. Common metadata fields include: source document ID, document title, author, creation date, section name, content type, language, confidentiality level, embeddings model version, etc. These are incredibly useful. First, metadata allows filtering at query time: e.g. department:"legal" or year:2022 can be used to restrict search results. Vector DBs universally support metadata filters (see Table A), so you can combine semantic similarity with boolean conditions. For example, a user asks a legal question and you only want to retrieve chunks from the “Legal” category of documents – simply add that filter to your query. This can dramatically reduce hallucinations by preventing irrelevant sources. (In one real incident, a chatbot gave a finance policy answer using an outdated policy document because the newer document wasn’t filtered properly by year.)

Second, metadata enables result re-scoring and aggregation. You can boost or group results by certain fields – e.g. prefer more recent documents by adding a time decay score, or ensure diversity by not returning 5 chunks all from the same document. The retrieval pipeline can use metadata to implement such business rules.

Metadata is also crucial for answer presentation and lineage: you’ll use it to display which document an answer came from (e.g. show the title or URL), and to trace back later which data was used. For audit and compliance, maintain a stable document ID for each source – ideally something like a hash of content – and store it in metadata. This allows you to track if a source has changed since it was last used, and to handle deletions (you can find all vector entries with a given docID and remove them if the document is redacted under GDPR, for example). One best practice is computing a SHA or MD5 hash of each document’s raw text and using that as an ID. This way, if someone modifies a document, it will get a new ID on re-ingestion, and you have an immutable reference to the exact content version that was embedded.

Finally, metadata can be exploited by the model prompt itself. Some systems will include a chunk’s metadata (like “Document: Project Apollo Internal Memo, Date: 1968”) as a preface to the chunk text. This can help the model decide how much to trust or how to use the information (e.g. if the date is old, maybe the assistant warns the user). It can also carry access-control info that the model (or a guardrail layer) checks. For instance, you might tag certain chunks as “confidential” and have a rule to not show them to external users. In summary: use metadata lavishly. It’s cheap (small strings or numbers) and immensely powerful for controlling retrieval and ensuring traceability.

Re-ranking for relevance: Even with good chunking and metadata, the initial vector search might return some results that are technically similar to the query but not truly relevant. Especially as your corpus grows, you’ll retrieve more “near misses” – chunks that share some terms or semantics with the query but don’t answer it. This is where an additional re-ranking model can boost quality. A re-ranker takes the top N results from the vector search (say 50 or 100) and evaluates each in light of the query, producing a new relevance score. Often this is a cross-encoder model (a smaller transformer that takes a [query, passage] pair and outputs a relevance score). Microsoft’s MonoT5, OpenAI’s GPT-3 (in classification mode), or Cohere’s ReRank API are examples. The re-ranker then outputs a sorted list where truly relevant items (even if they were vector-ranked 5th or 10th) bubble to the top. This improves the precision of the final context given to the LLM, which in turn means the LLM is more likely to find the answer without hallucinating. NVIDIA’s research showed that “re-ranking…enhance[s] the relevance of search results by using the advanced language understanding of LLMs.” Essentially, a re-ranker is like a smarter judge that corrects the rough ordering done by the ANN search. In practice, teams have found significant gains: one LinkedIn post notes “The reranker… reorders the top 100 candidates… Precision up, hallucinations down.”.

There are different re-ranking strategies: Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF) is a light-weight method to fuse multiple result lists (like lexical vs vector) without a heavy model – Qdrant uses this internally for hybrid search. It gives a simple way to boost documents that appear in both the BM25 and vector top lists, for example.

On the other hand, neural re-rankers (cross-encoders) actually read the chunks and the query together to judge relevance, which is more powerful but computationally heavier. With the rise of LLMs, some teams even use the main LLM itself to re-rank (by asking it to pick the most relevant snippets before answering), though this can be slow and costly. A practical approach is to use a smaller dedicated model – e.g. a MiniLM or Electra-based cross-encoder fine-tuned on MS MARCO data – which can re-rank 100 passages in a few hundred milliseconds. That adds a bit of latency, but you might then only send the top 3–5 to the final LLM instead of top 10, resulting in a smaller prompt and offsetting the cost.

The need for re-ranking depends on your corpus and domain. If your initial retrieval is very accurate (like a well-scoped FAQ DB), you might skip it. But for broad corpora (enterprise-wide knowledge bases, web data, etc.), it’s almost essential for high-quality results. As one 2026 case study noted, companies that “swapped algorithms for embedding, chunking, and retrieval” without success discovered that the missing piece was proper retrieval engineering – including re-rankers and evaluation. The trade-off is complexity and cost, so measure the impact. You can A/B test your pipeline with and without re-ranking using metrics like Precision@K or MRR on a set of queries. If re-ranking significantly improves precision@3, it’s probably worth the extra milliseconds.

Domain-specific embedding & recall tricks: One more thing “that actually works” – using domain-tuned embeddings or hybrid retrieval to improve recall for niche content. Off-the-shelf embedding models (like OpenAI’s or SBERT) might miss subtle domain connections. For example, in legal text, specific jargon or citations are key; in code, variable names and structure matter. It’s been observed that “general-purpose embeddings are often insufficient” and you may need “domain-specific embedding strategies… including fine-tuned models or hybrid lexical-semantic representations to capture precise meaning.” This could mean fine-tuning an embedding model on your domain documents (if you have the data), or simply combining embeddings with a traditional keyword index. Many production RAG systems use hybrid retrieval (discussed earlier) – essentially they don’t trust vector search alone for 100% recall. For instance, a medical chatbot might use a symptoms ontology to tag and filter documents, or a code assistant might do an exact keyword search for function names in addition to embeddings. Our vector DB comparison showed Weaviate, Qdrant, Pinecone all now support hybrid search modes (either via RRF or sparse-dense indexes).

Leverage these features. They can dramatically improve quality for queries where specific terms matter (e.g. error codes, proper nouns). And they add minimal overhead – Pinecone’s sparse-dense index, for example, lets you do hybrid search with the same API call, weighting dense vs sparse components as needed.

In summary, smart chunking, rich metadata, and re-ranking form a triad of techniques that elevate your retrieval performance to an enterprise-grade level. With these in place, you give the model the best possible shot at answering correctly. Now we’ll turn to how you keep this whole system fresh, auditable, and maintainable over time – via data pipelines and governance.

5. ETL/ELT & Orchestration: Keep It Fresh and Auditable

Building the knowledge base is not a one-and-done task – it’s an ongoing process of extraction, loading, and transformation (ETL/ELT) as your data evolves. In this section, we discuss how to keep your embeddings up-to-date and your pipeline auditable using orchestration frameworks and “lakehouse” storage. We’ll also compare Airflow vs Dagster for workflow orchestration and Delta Lake vs Apache Iceberg for managing data on cloud storage (Table B).

Continuous ingestion pipelines: In a dynamic environment, new documents appear, and old ones get updated or deleted. Your AI should reflect those changes promptly. That means setting up a periodic pipeline (or event-driven triggers) to ingest data, embed it, and index it. For example, you might schedule an Airflow DAG to run every night which pulls the latest documents from a source (CMS, database, file system), processes them into chunks, generates embeddings, and upserts them into the vector DB. Or you might use streaming – e.g. an API call triggers embedding as soon as a new document is uploaded. The choice depends on how real-time it needs to be. Many enterprise use cases can tolerate a few hours of lag (nightly or hourly updates), while others (like a customer chat using newly submitted tickets) require near-real-time indexing.

Orchestration frameworks: Tools like Apache Airflow and Dagster greatly assist in managing these pipelines. They handle scheduling, retries, dependencies between tasks, and logging – so you have a reliable “data factory” feeding your AI. Here’s a quick comparison:

Orchestration & Lakehouse Summary

Both Airflow and Dagster can certainly handle AI data pipelines (ingesting documents, updating vectors, retraining models, etc.). Airflow is often the default in enterprises (it’s been around longer), but Dagster is seeing adoption for its developer-friendly features. To illustrate: if you want to ingest new documents nightly, Airflow might have you write a DAG with tasks like “extract files -> chunk & embed -> upsert to DB -> verify counts.” Dagster would let you define these as software assets (raw_docs, processed_chunks, index_state) and not worry as much about the control flow – it figures out the order from dependencies. The choice may come down to your team’s familiarity and the rest of your stack. There’s no wrong answer; either can make your life easier than scripting cron jobs manually. What’s important is that you do set up a governed process rather than ad-hoc updates. That process should include logging and alerts (e.g. if embedding fails for some files, alert the team) and ideally automated tests (perhaps using a small set of documents to ensure the pipeline outputs expected embeddings and retrieval results).

Data Lakehouse for auditability: When we say “keep it auditable,” we mean you should be able to trace what data was present at any given time and reproduce results if needed. This is where using a transactional data lake format helps. Technologies like Delta Lake and Apache Iceberg provide a structured, versioned storage layer on top of cloud object stores (S3, Azure Blob, etc.). Instead of dumping processed text into random JSON files or a NoSQL store, you can store them in a Delta/Iceberg table, which gives ACID transactions and time-travel queries. For example, your pipeline writes all cleaned, chunked text to a Delta Lake table “document_chunks”. Each run that ingests new or updated docs does an upsert (Delta and Iceberg support UPSERT/MERGE operations). This means the table’s state is snapshot at each run – you can query “what did document_chunks contain last week?” easily. If a bug in processing introduces bad data, you can roll back to a previous version. Moreover, these table formats ensure consistency: if your pipeline fails halfway, you won’t end up with half an index updated – the transaction will roll back or not be committed. This pairs nicely with the vector DB: you might use the Delta table as the source of truth and rebuild the vector index from it if needed, or cross-check that every vector entry has a corresponding row in the table.

Another benefit is performance and scaling. Both Delta and Iceberg are designed for big data – you can store millions of chunks efficiently and query them via Spark, Trino, etc. For example, if you want to do an analytics query like “how many documents of each category were added in 2025?”, that’s easy on a Lakehouse table but hard if your data is siloed in a vector DB. The Lakehouse can also feed model training: say you want to fine-tune an LLM on your document text – you can snapshot the Delta table and use that as training data, knowing exactly which version of content you used. Meanwhile, the vector index can be updated incrementally by reading only the new/changed rows (Delta and Iceberg both support change capture or you can diff versions).

Delta vs. Iceberg: Both are excellent open table formats, but a few differences (see Table B):

Lakehouse Table Formats: Delta Lake vs. Apache Iceberg

For our context (GenAI data pipeline), both Delta and Iceberg will serve well as the structured backend for document storage. They ensure that as you add or update documents, you have a clear history and consistent state. Suppose an EU regulator asks, “what knowledge did your AI have about Person X on July 1, 2025?” – if you’ve been storing your ingested data in a versioned table, you can actually answer that by querying the snapshot as of that date. If you had just been updating a NoSQL store or the vector DB directly, it would be much harder to reconstruct that historical view.

Putting it together: A recommended pattern is to treat your document corpus like any other critical data asset: maintain it in a lakehouse table with ACID properties, and have an orchestrated ETL that keeps the vector index in sync with that table. For example, an Airflow DAG could (1) pull new docs into a raw Bronze table, (2) transform and chunk into a Silver table (with Delta/Iceberg), then (3) call a task to upsert those chunks into the vector DB, and finally (4) mark the new version of the table. The vector IDs can include the document hash or table partition as metadata, creating a linkage between the vector entry and the exact source version. This might sound heavy, but it pays off whenever you need to troubleshoot or audit. It also helps with freshness: since you’re regularly ingesting, you can ensure that (for example) any document updated in the source will be re-embedded and replace the old content. Some teams even automate a full re-index if data changes radically (though that can be expensive – better to target updates).

We’ve now covered how to manage the data pipeline. In the next section, we’ll talk about governance: privacy, quality, lineage, and data residency considerations, especially pertinent to jurisdictions like the EU and Israel.

6. Data Governance: Privacy, Quality, Lineage, and Residency (EU/IL)

When deploying AI systems in the real world, especially in regulated environments (finance, healthcare, government), it’s not just about technical performance – governance is paramount. This encompasses privacy protection, data quality control, lineage tracking, and ensuring data stays in allowed regions. Let’s break these down and highlight some best practices, with focus on EU and Israeli contexts.

Privacy and compliance: If your AI is using personal or sensitive data, you must adhere to laws like GDPR in the EU and similar regulations in other jurisdictions. GDPR, for instance, requires a lawful basis for processing personal data and gives individuals rights like access and erasure. An AI chatbot that might surface personal data from documents could easily violate these if not carefully designed. Some guidelines for privacy:

- Minimize sensitive data in the knowledge base. During ingestion, consider scrubbing or pseudonymizing PII (Personally Identifiable Information) if it’s not crucial for AI functionality. For example, replace actual names with an identifier, or mask account numbers except last 4 digits. This reduces the risk if the model output ever strays. There are tools that can detect PII in text; integrate them in your pipeline to tag or remove sensitive fields.

- Access control filters: As noted earlier, implement fine-grained metadata-based access controls in retrieval. If certain documents are confidential or user-specific, tag them with access levels and filter results based on the querying user’s identity/role. For instance, a customer support AI might have access to general FAQ answers for anyone, but account-specific info (orders, tickets) should only be retrieved when an authenticated user session with that account is present. Vector DBs and retrieval logic should enforce this. If using RAG internally, ensure the user context is passed to filter out anything the user shouldn’t see.

- No training on user data unless opted-in: If you’re using third-party APIs (like an LLM API), be mindful of their data usage policies. OpenAI, for example, has stated that API data is not used to train models by default (unless you opt in), but you should verify and possibly execute a Data Processing Agreement. For EU personal data, you might prefer a local deployment or a provider that explicitly hosts in the EU with GDPR compliance. Microsoft Azure, for instance, offers OpenAI service in EU data centers with GDPR compliance – this can be an option to keep data residency in check while using powerful models.

- Right to be forgotten: Prepare a mechanism to delete an individual’s data if requested. This means if someone invokes GDPR Article 17 (erasure), you should be able to find all vectors and documents related to that person and remove them. This is easier if you’ve tagged personal data in metadata (e.g. a “user_id” field on chunks from a specific user) or use a content hash/ID to identify documents about that person. Remove from both the source table (Delta/Iceberg) and the vector index, and confirm it’s gone (some vector DBs, like Pinecone, might have soft delete vs hard delete – ensure compliance by true deletion or reindexing). Keep in mind backups too – data should be erased from backups in a reasonable timeframe or excluded from use.

- Content moderation: Consider implementing guardrails at generation time to avoid exposing sensitive info. For example, before showing the model’s answer to the user, run a check: does it contain any policy-violating content? (OpenAI and others provide moderation models for this). If the model tries to regurgitate some personal data that it saw in context, your system could catch that and filter or redact it. While this is more on the output side, it’s a governance measure to prevent leakage of personal or confidential data that made it past input filters.

Data quality: Quality in = quality out. Your retrieval layer should include processes to maintain high data quality in the knowledge base:

- Source verification: Prefer trusted, canonical data sources. For instance, use official policy documents or databases rather than user-entered free text (which might have errors) when possible. If multiple sources have conflicting info, decide which is authoritative and perhaps exclude the others to avoid confusion.

- Data cleaning: Remove duplicates and irrelevant content during ingestion. If the same document (or very similar text) is indexed multiple times, it can bias retrieval or waste context window. Ensure your pipeline can detect duplicate files (content hash helps) and skip or consolidate them. Also filter out obviously noisy text (like boilerplate footers, navigation menus from web pages, etc.) so they don’t pollute search results.

- Human in the loop: For critical knowledge bases, you might involve subject matter experts to review what goes in. For example, before deploying an internal HR chatbot, the HR team might review the embedded content for accuracy and completeness. At least, provide tools for them to update content if an answer is wrong (this often means updating a document and re-running ingestion, which your pipeline should allow easily).

- Continuous evaluation: We will detail tests in the next section’s checklist, but governance includes regularly evaluating retrieval quality. Monitor for queries that had poor results or where users gave feedback. Use those to improve the data (maybe a missing document needs adding, or an irrelevant doc needs exclusion). Some organizations set up regular audits of AI answers: e.g. sample 50 Q&A pairs a week and have reviewers check if the sources support the answer and if not, pinpoint whether retrieval or the model was at fault.

- Lineage and versioning: As discussed in section 5, keeping track of data versions is crucial. If a mistake is found (say the bot is quoting an old regulation), you want to trace which document and which version that came from. By storing data in a versioned store and logging query -> retrieved doc IDs, you can backtrack. Lineage also means if the output is incorrect, you can figure out was it because the data was wrong (garbage in) or because the model misused correct data. For debugging and compliance, maintain logs of the context used for each answer (at least in internal systems – for public ones that might be too much data, but you could log for problematic cases or sampling). This will let you answer the classic question: “Why did the AI say that?” by showing “It said that because document XYZ (version 3) had that text.”

- Reproducibility: In some cases, especially in industries like finance, you may need to reproduce a result exactly (for audit or legal challenge). This is hard with LLMs due to their nondeterminism, but you can at least ensure the retrieval was deterministic by versioning data and recording seeds/prompts. Some teams address this by using the same snapshot of data for both training and answering questions in a given period. This might be overkill for most, but worth noting.

Data residency (EU/IL focus): Data residency refers to keeping data within certain geographic boundaries. The EU’s GDPR effectively requires that personal data of EU individuals be either kept in the EU or only transferred to countries with adequate protections (or under specific contractual clauses). Israel, while not in the EU, has its own privacy law (Protection of Privacy Law) and as of 2025 is deemed to have adequate protection by the EU (Israel’s laws are somewhat aligned with GDPR). However, Israeli regulators and clients often require that sensitive data (especially in sectors like defense or healthcare) remain in Israel or at least not go to certain other jurisdictions.

To comply, you should:

- Choose regional services carefully: If using a managed vector DB or LLM API, pick an EU region deployment. For example, Weaviate Cloud offers EU clusters (e.g. in Frankfurt), Qdrant Cloud as well (and they market compliance like SOC2 and even HIPAA). Pinecone has an EU (Frankfurt) option for indexes. Ensure your data is stored and processed on those regional servers. For Israeli data, currently there may not be Israel-based cloud AI services (the big providers are expanding to IL regions for general compute, but AI APIs might not be there yet). One approach is to host open-source solutions on infrastructure in Israel. For instance, an Israeli bank might run Qdrant on their own servers in Israel and use an open-source LLM locally (to avoid sending data abroad). If using a cloud LLM not in IL, maybe opt for an EU instance which at least falls under GDPR and is legally allowed for transfer to Israel (as the EU recognizes Israel’s privacy laws).

- Avoid transferring personal data outside allowed zones: This might mean turning off certain analytics or logging that sends data to a central (non-EU) server. If you use SaaS tools in your pipeline (like a cloud OCR or a monitoring service), check where they store data. Often, self-hosted or on-prem alternatives are chosen in these cases.

- Encryption and security: As part of compliance, use encryption at rest and in transit. All the vector DBs support encryption; if self-hosting, use disk encryption and TLS. If you have to work with an external provider, encrypt the content before sending if possible (though encrypted vectors that still allow similarity search is an active research area – most practical approach is to rely on provider’s security). Also implement access controls so only authorized personnel or services can access the data stores. These measures won’t solve legal residency requirements, but they demonstrate due diligence and mitigate risk of breaches (which are reportable under GDPR).

- Localizing models: One often overlooked aspect – if you are using a global model (like GPT-4) with local data, be mindful of localization. For instance, EU has strict rules on using personal data for training. If you fine-tune a model on EU personal data, you might inadvertently create a new dataset that has to stay in region. Even if not fine-tuning, some companies opt for local inference for anything involving sensitive data. Running a model in a data center in the EU/IL ensures the prompts and generations don’t leave. Open-source LLMs (like Llama 2, etc.) can be deployed on-prem for this purpose. It’s a trade-off (they may not be as powerful as GPT-4, or might require significant infra), but it’s becoming feasible for many use cases with 2025 hardware and models.

- Regulatory requirements: In sectors, you might have to keep audit logs (e.g. who accessed what data). Make sure your retrieval layer can log query access to certain documents (this intersects with lineage logging). Some regulations might also require human oversight over AI decisions – an auditable retrieval pipeline makes that easier, because a human can review which docs the AI considered.

- Certifications: If you’re in healthcare (HIPAA in the US, or analogous requirements in EU/IL) or finance, you might need your data pipeline to comply with certain standards. For example, if using a vector DB SaaS, ensure they are HIPAA compliant or ISO27001 certified, etc., as needed. Many vector DB companies have obtained certifications to ease enterprise adoption (e.g. Weaviate Cloud HIPAA on AWS, Qdrant Cloud SOC2 and stating HIPAA readiness). This doesn’t automatically make you compliant, but it’s necessary due diligence.

In summary, governance is about making your AI not just smart, but also safe, lawful, and trustworthy. The retrieval layer is where you enforce a lot of those policies: what data goes in (quality), what data comes out (no private info leakage), and where data lives (residency). By planning for these from the start – using strong metadata, access controls, region-aware deployments, and audit logs – you can avoid nasty surprises when the auditors or regulators come knocking.

Finally, to ensure everything is working as intended, let’s turn to a practical checklist for testing your retrieval system’s quality.

7. Hands-On: Retrieval Quality Test Checklist

How do you know your retrieval-augmented AI system is actually performing well? Here’s a checklist of tests and evaluations you can (and should) run. These tests ensure your data layer is delivering relevant, fresh, and safe results to the model. The list is “copy-paste ready” – feel free to use it as a template for your QA process:

- [ ] Relevance accuracy (ground truth test): Compile a set of question–answer pairs where you know which document or source contains the answer. For each question, check if that correct document is present in the top K retrieved results (e.g. top 3 or top 5). This evaluates recall@K for your retrieval. Aim for high recall here – the correct answer must be retrieved; otherwise the model has no chance. Use metrics like Precision@K or Recall@K on this set.

- [ ] Precision and noise check: Manually review a sample of retrieval results for various queries. Are the retrieved passages on-topic and useful, or are some clearly irrelevant? If you find irrelevant chunks frequently in the top results, consider tightening similarity thresholds, improving embeddings, or using a re-ranker. This helps gauge precision (how many of the top results are actually relevant).

- [ ] Synonym and lexical coverage test: Come up with queries that use synonyms or different wording than your documents. For example, if documents say “COVID-19” and user asks “coronavirus”, or doc says “income statement” and query says “P&L”. Test whether your retrieval still finds the right info (a pure keyword search might fail, but your embeddings should handle it). If it fails, you might need to enrich documents with synonyms (in metadata) or use a hybrid search approach.

- [ ] Filter efficacy test: If you have metadata filters (e.g. a date or category filter), test queries with and without the filter. For example, a query for “Privacy Policy” vs the same query with filter region: EU. Verify that the filter indeed restricts results (you should not see documents outside the EU region in that example). Also test role-based filters by simulating different user roles to ensure unauthorized data isn’t retrieved.

- [ ] Freshness test: Add a new document (or update an existing one) with some known Q&A content. After your pipeline runs, ask a question that’s answered by that new/updated content. The system should retrieve the new info, not stale info. This tests that your ingestion and indexing are keeping up. For example, if you update a policy document’s answer, the old answer chunk should no longer appear – only the new one.

- [ ] “No answer” handling: Ask a question that you know is not answered in the knowledge base. The retrieval should ideally return either no results or very low similarity scores, and your system should handle this gracefully (perhaps the AI says “I don’t know that” or falls back to a default). Ensure that in these cases you’re not getting some random semi-related chunk that could mislead the model into hallucinating an answer. If you do see a random chunk retrieved, consider adjusting similarity score cut-offs or adding a rule: if top score < X, treat it as no-answer.

- [ ] Multi-turn consistency check: If your system is conversational (maintains dialogue context), test that retrieval works in follow-up questions that refer to previous answers. For instance, Q: “What does the 2022 report say about revenue?” (system retrieves from 2022 report). User: “How about profit?” – the system should understand this refers to 2022 report’s profit and retrieve accordingly. This involves query context handling in your app, but touches the retrieval if you carry over relevant metadata or previous query results.

- [ ] Scaling and latency test: As a load test, perform a batch of retrieval queries representative of real use (you can script this). Measure the response times and throughput (QPS). Does latency stay within acceptable range (e.g. P95 under 200ms for retrieval)? If not, identify bottlenecks – maybe you need to add an index, more replicas, or enable caching. Also monitor memory/CPU of your vector DB during this test to see if it’s near limits.

- [ ] Cost test: If using a paid service (like Pinecone or an LLM API as reranker), monitor how cost scales with queries. E.g. turn on the re-ranker and run 100 queries, then off for 100 queries, compare cost and accuracy. Ensure the quality gain from re-ranking or hybrid justifies the added cost. Similarly, test different K values (how many neighbors) – maybe retrieving 5 vs 10 vs 20 and see if more context actually improves answers or just adds cost.

- [ ] Edge case queries: Test queries that are tricky: very short queries (one word), very long queries, queries with typos, and multi-language queries (if applicable). See how retrieval handles them. Typos might require using a model that’s robust or having a spelling correction step. Multi-language: if your embeddings are multilingual (like multilingual MPNet or similar), test that (e.g. ask the question in Spanish and see if it retrieves the English doc). If it fails, you might need a translation step or a multilingual model.

- [ ] Hallucination stress test: Identify some known areas where the model might be tempted to hallucinate – typically where the knowledge base is thin or the query is slightly out of scope. For these, observe the behavior. Does retrieval pull in something tangential that might lead the model off-track? If yes, consider adding guardrail prompts (like “If you don’t know, say you don’t know”) or expanding the knowledge base in that area. Essentially, use these tests to see how retrieval (or lack thereof) contributes to any hallucinations.

- [ ] Delete/update test: Delete a document (that was frequently retrieved) from the knowledge base and run the pipeline to remove it from index. Then ask a question that previously had an answer from that doc. The system should no longer retrieve content from the deleted source. This tests the “right to be forgotten” capability and ensures no ghost data lingers. Similarly, update a document’s content and verify old content isn’t retrieved.

- [ ] Security & privacy test: Try a query that should be disallowed or filtered (e.g. asking for someone’s personal data that the AI shouldn’t reveal, or using an offensive term). Check that either nothing is retrieved (if you filtered such content) or that the generation module catches it. For instance, if a confidential doc exists but user doesn’t have access, make sure retrieval returns nothing (and ideally the AI says it can’t answer). This verifies your privacy guards in the retrieval layer.

By running through these tests regularly (especially after changes to data or model), you can catch problems early. Automate what you can – for example, have a nightly job that calculates retrieval accuracy metrics on a test set and alerts if it drops below a threshold. As Qdrant’s team noted, “None of the experiments make sense if you don’t measure the quality… use standard metrics such as precision@k, MRR, NDCG” to evaluate search effectiveness. A library like ranx can help compute these if you have labeled data. In essence, treat your retrieval system as a product that requires ongoing QA and tuning.

8. Putting It Together: Two Reference Blueprints

To cement all these concepts, let’s sketch two reference architecture blueprints for a data & retrieval layer in GenAI systems. These blueprints illustrate how you might combine the components we discussed (vector DB, document store, pipelines, etc.) in real-world scenarios. One is a cloud-native approach using managed services, and the other is a self-hosted approach for maximum control (often driven by compliance needs).

Blueprint A: Cloud-Native RAG Stack (Managed Services)

Use case: A company wants to build a customer support AI assistant that can answer questions using company knowledge (product manuals, help center articles, policy documents). Speed to market is important, and they prefer managed services to offload ops. However, they must ensure EU user data stays in Europe (GDPR compliance) since they have many EU customers.

Architecture: This stack uses mostly cloud-hosted components with regional configuration:

- Data storage: All source documents (PDF manuals, HTML guides, etc.) are stored in an EU-based S3 bucket (or Azure Blob in EU). This is the primary document store. Additionally, a Delta Lake table is maintained on this storage to keep a structured index of documents and their chunked text (for audit/versioning).

- Vector database: Use Pinecone (managed vector DB) with an index hosted in eu-west (Frankfurt). Pinecone will store embeddings for each document chunk along with metadata (e.g. document_id, title, etc.). We choose Pinecone for ease of scaling and its hybrid search capability – we will use its new sparse-dense hybrid index to improve results for keyword-heavy queries. All data sent to Pinecone (embeddings, metadata) stays in Frankfurt data centers, satisfying residency.

- Model API: Use OpenAI GPT-4 via Azure OpenAI Service, deployed in West Europe region. This gives us a state-of-the-art model with 32k context window, hosted in EU. The model API will not log or use our prompts for training (per OpenAI’s policy for Azure). We’ll also leverage OpenAI’s built-in content filtering for generation.

- Orchestration & pipeline: Use Azure Data Factory or GitHub Actions to trigger a daily update pipeline (for simplicity – Airflow/Dagster could be used too, but perhaps the team chooses Azure Data Factory since they are already on Azure). The pipeline does: (1) scan the source bucket for new/updated files, (2) extract text from files (using an OCR or text extract service if needed), (3) split into chunks (respecting headings and sections, using a Python script), (4) upsert new chunks into the Delta Lake table (with versioning), and (5) generate embeddings for new chunks using OpenAI’s embedding model (e.g. text-embedding-ada-002 via API). These embeddings are then upserted to Pinecone with the chunk metadata. This pipeline also logs what it did (how many docs processed, etc.).

- Retrieval workflow: When a user question comes in to the app (either via a chatbot UI or API), the backend performs retrieval:

- It first formulates any metadata filter – e.g. if the user is asking about a specific product, it might filter by product category. It also might extract keywords from the query for hybrid search.

- It calls Pinecone’s query endpoint with the user’s question embedding (from the same OpenAI embedding model) and the sparse terms. Pinecone’s index, being sparse-dense, handles this and returns, say, top 10 candidate chunks with combined scores.

- The backend then applies a re-ranking step: it takes those 10 chunks and feeds them (with the question) into a smaller re-rank model. For simplicity, they decide to use OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 (which is cheaper) to score each chunk relevance by asking it (in a few-shot prompt) to rate how well the chunk answers the question. Alternatively, they could use a open-source model like Cohere Rerank or MonoT5 if latency allows. The chunks are re-ordered accordingly.

- Now take the top 3 chunks and construct the prompt for GPT-4: e.g. “You are an assistant... <user question> ... Here are relevant excerpts: <chunk1> ... <chunk2>... Provide answer with references.” They include the metadata (doc title) so GPT-4 can cite it.

- GPT-4 generates an answer, which is then post-processed to ensure no policy violation (OpenAI’s content filter is automatically checking, but they also implement their own check for certain keywords).

- The answer with citations is returned to the user.

- Governance: All interactions are logged. For each answer, they log which document IDs were retrieved and the final answer. This log is stored in an EU database. If a user requests data deletion, they can look up which documents relate to that user (e.g. username or email is part of metadata) and remove them from S3/Delta and Pinecone. Pinecone’s delete API is called to remove vectors by metadata filter (e.g. all chunks with user_id = X). Since Pinecone is just an index, the canonical data removal is actually from the source bucket and Delta table, which they version as “removed”. Pinecone is then just reflecting that state.

Why this works: This blueprint leverages high-level services so the team can focus on the application, not infrastructure. It ensures EU residency by configuring both storage, vector DB, and model in Europe. The use of Azure OpenAI in EU and Pinecone in EU addresses compliance concerns. The pipeline running daily keeps data fresh (if needed, they could run it more often or even event-driven if someone uploads a doc). And importantly, the blueprint includes multiple layers to maximize quality: hybrid search (to catch lexical cues), re-ranking with a language model, and guardrails. This design is similar to what many companies implemented in 2024–2025 for enterprise QA bots. For example, Morgan Stanley’s famous internal GPT-4 assistant followed a comparable approach: they augmented GPT-4 with a vector-index over tens of thousands of internal documents, enabling advisors to ask “effectively any question” over their corpus and get reliable answers. Our blueprint A aligns with that pattern – a powerful cloud LLM grounded by a curated vector search on proprietary data.

Check out a related article:

Generative AI Like ChatGPT: What Tech Leaders Need to Know

Potential variations: If cost is a big concern, the team could use GPT-3.5 for answering instead of GPT-4 (with some accuracy trade-off), or use a smaller open-source model hosted on Azure VMs. Pinecone could be swapped with Weaviate Cloud if they prefer open source (Weaviate also offers a hybrid search and even has a built-in generative module now). The overall cloud-managed philosophy remains.

Blueprint B: Self-Hosted Secure RAG Stack (On-Premises/Open Source)

Use case: A government agency or bank in Israel is building an internal AI assistant for employees to query sensitive internal documents (e.g. legal contracts, R&D reports, financial plans). Privacy is paramount – no data can be sent to external services or leave the country. They also want full control to customize the system.

Architecture: This stack is deployed on the organization’s own servers (or a private cloud), using open-source components:

- Data storage: A PostgreSQL database with the pgvector extension or an Apache Iceberg table on a private object store is used to store the documents and chunks. Let’s say they use an Iceberg table on MinIO (an S3-compatible storage) hosted in their data center. All documents (in PDF, Word, etc.) are stored in a secure file repository, and the text chunks with metadata are stored in the Iceberg table for easy querying and versioning.

- Vector database: They deploy Qdrant on-premises (Docker/Kubernetes), within their secured network. Qdrant is chosen for its strong filtering and hybrid search support while being self-hostable in an air-gapped environment (and its Rust core is efficient). They configure Qdrant to use HNSW index with persistence on disk (since data might be large). Qdrant will store embeddings for each chunk plus metadata like doc_id, classification level, etc. If needed, they also run a separate Elasticsearch instance for advanced keyword search (though Qdrant’s built-in RRF hybrid might suffice for textual data, augmented by storing sparse vectors for BM25 in Qdrant itself).

- Model deployment: For absolutely no external data transfer, they use a local LLM. They obtain a 13-billion-parameter open-source model (such as LLaMA 2 or an AI21 Jurassic model variant) and fine-tune it on their internal data or instructions if necessary. This model is hosted on an internal GPU server. The context window might be smaller (say 4k tokens), so they plan to be efficient with retrieval. For embeddings, they also use a local model – perhaps a MiniLM or Instructor model for generating vector embeddings (so that embedding generation doesn’t call an external API). These models run on GPU servers as microservices accessible within the network.

- Orchestration & pipeline: They run Apache Airflow on-prem to orchestrate nightly ETL. Airflow fetches any new or updated documents from various internal data sources (shared drives, SharePoint, databases) – this can be done via sensors or a simple scheduled DAG. The pipeline then cleans and chunks the documents (they have a custom chunking script that respects document structure, possibly using an NLP library to split by sections). Chunks are written to the Iceberg table (with a new snapshot created). Then another task computes embeddings for each new chunk using the local embedding model server. Finally, those embeddings are upserted into Qdrant via its API. They also compute a sparse vector (like BM25 weights) for each chunk using Elasticsearch’s analysis – these are stored in Qdrant as well to enable hybrid search. The pipeline, being internal, can be more tightly integrated – for example, as it writes to Iceberg it could trigger an update to Qdrant.

- Retrieval workflow: When an employee asks a question (via a chat UI or search interface), the backend application performs:

- Query classification: Determine if the question might need a certain filter (e.g. if the question is “show me Alice’s performance review,” that might be HR confidential – the system should check the user’s role and apply a filter for documents accessible to that user). The user’s ID and permissions are known since it’s internal auth.

- It then queries Qdrant. They use Qdrant’s new multi-vector query API to do a hybrid search: the query is embedded with the local embedding model, and also broken into keywords for a sparse query. Qdrant combines the dense and sparse results using RRF. They also include a filter in the query for document classification <= the user’s clearance level (thanks to Qdrant’s metadata filtering).

- Qdrant returns, say, 15 candidates. They choose to use an LLM-based re-ranker internally. They have fine-tuned a smaller 3B parameter model to act as a reranker (or they use the same 13B model in a classification mode). The application passes the question and each chunk to this reranker model (running locally on a GPU) to score relevance. It then selects the top 5 chunks.

- The top chunks are concatenated (with some prompt template) and fed into the main LLaMA 2 (13B) model to generate the answer. Since the model is internal, they’ve also fine-tuned it to style answers formally and include source references (or they use a prompt pattern to have it output, like “[Source: Document ABC]” references).

- The answer is returned. Since this is internal, they log everything. They also apply a final check: if the answer contains something the user isn’t allowed to see (maybe extremely unlikely because retrieval filtered, but just in case), they have a rule-based scanner (e.g. if the answer text contains “[Confidential]” tag from a document and user isn’t privileged, it withholds it).

- Governance: Because all data and models are in-house, compliance is easier in terms of no external exposure. They maintain strict lineage: every chunk in Iceberg has a source document ID and version. Airflow logs which docs were processed each run. They can trace any answer through the logs to which chunks and documents were used. They keep old snapshots of the Iceberg table, so they can reconstruct, for example, last month’s state of knowledge. For privacy, if someone’s personal data is in a document and needs deletion, they can remove it from the source and re-run ingestion – the pipeline will calculate a new hash for the modified doc, so the old chunks get deleted (Airflow can call a delete on Qdrant by docID). They also plan periodic quality audits: a team of domain experts reviews a sample of Q&A pairs the system produced and gives feedback, which is then used to refine the chunking or add missing documents.

Why this works: This blueprint prioritizes security and control at the expense of some convenience. By self-hosting everything, the organization ensures no data leaves their environment – a must for sensitive info. It uses proven open-source tech: Qdrant for similarity search (with its robust fusion and filtering), Iceberg for data management, and local LLMs for generation. While the local LLM may not be as powerful as GPT-4, the retrieval augmentation narrows its task so that a smaller model can still perform well on domain-specific queries (plus no risk of OpenAI seeing the prompts). This mirrors approaches taken by organizations who cannot use cloud SaaS. For instance, some banks have combined open-source LLMs + vector DB on-prem to build internal assistants, accepting a slight quality hit for the sake of data governance. Our blueprint B is essentially an enterprise AI stack behind the firewall. Companies like Neople (a game publisher) have used Weaviate (open-source) to power an internal QA system, and many others in 2025 opted for self-hosted Qdrant or Milvus with local models for privacy. The technology is mature enough that an open solution can handle tens of millions of documents if needed, with optimizations.

Potential variations: If the data wasn’t as sensitive, they might use a third-party model via a secured channel (for example, AI21 Labs has models available, being an Israeli company, some Israeli orgs consider using AI21’s model endpoints if they sign DPAs – but in our strict scenario, we kept everything internal). They could also use pgvector in Postgres for vector search if the scale is small and they want simplicity (some smaller deployments do this to avoid running a separate vector DB). However, Qdrant’s extra features (RRF, etc.) likely justify its use here. Orchestration could be Dagster if they prefer its data asset tracking, but Airflow is fine and widely used in such orgs.

Both Blueprint A and B implement the core principles we covered: chunk intelligently, use metadata and filters, incorporate re-ranking, maintain a data store of truth, and monitor quality. They just do so with different tool choices based on constraints.

These reference architectures provide a blueprint, but of course each project will have nuances. You can mix and match elements – e.g. a hybrid of these might be using a managed vector DB but a self-hosted model, etc. The key is to align the stack with your needs on quality, cost, and compliance.

No matter which path you choose, one thing is clear: the Data & Retrieval layer is the linchpin for real-world AI solutions. With a strong foundation here, your models will produce far more reliable and effective outcomes. By combining the strategies we’ve discussed – from vector DB selection and hybrid search, to careful data governance and iterative testing – CTOs and architects can deliver AI systems that are not only intelligent, but also trustworthy, efficient, and compliant.

Looking to implement a tailored AI stack for your organization? Intersog is an experienced AI software development company that can help design and build your solution, from data pipelines to custom AI models.

Leave a Comment