Although blockchain is best known for enabling cryptocurrencies, the underlying design - a shared, append-only ledger maintained across multiple computers - has far wider applications. Distributed ledgers can eliminate the need for trusted intermediaries, enhance transparency and cut reconciliation costs. Since this technology debuted with Bitcoin in 2009, several architectural patterns have emerged. Understanding these patterns helps innovators select the right foundation for their product or platform.

This article first explores permissioned versus permissionless architectures, before examining the four major types of blockchain - public, private, consortium and hybrid - in depth. For each type, we outline the relevant governance model, benefits, drawbacks, use cases and examples. We also provide a decision framework, highlight common mistakes and answer frequently asked questions.

Permissioned vs permissionless

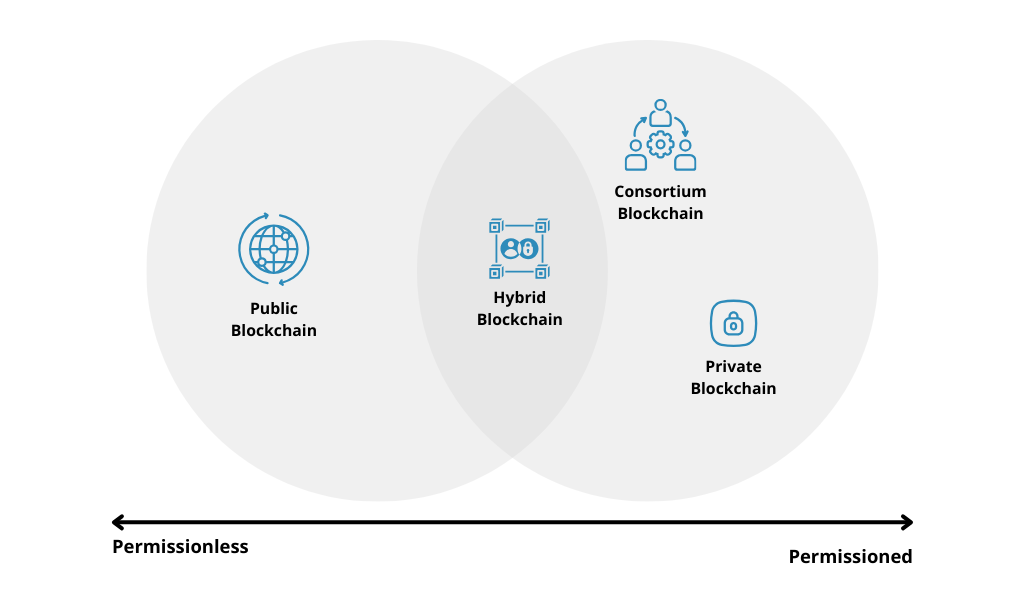

Blockchain networks can be broadly categorized as permissionless or permissioned, a distinction that determines who can publish blocks, read data and participate in consensus.

Permissionless networks

In a permissionless network, anyone can join and publish new blocks, as well as submit transactions, without needing approval. NIST likens this model to the public internet: if anyone can publish a new block, the network is permissionless. As participation is open, these networks must anticipate malicious behaviour and therefore employ consensus protocols such as Proof-of-Work or Proof-of-Stake to deter such actors. All participants can read the ledger and create transactions, which results in high transparency, but also slower throughput and higher energy consumption. Popular examples include Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Permissioned networks

A permissioned blockchain restricts who can publish blocks and who can read data. According to NIST, if only certain users can publish blocks, the network is permissioned. However, permissioned networks can still allow anyone to read the ledger or submit confidentiality are priorities.

It is important to note that 'permissioned' and 'permissionless' describe access and governance models, not the four network types themselves. As the following sections show, both public and private networks can be either permissionless or permissioned. Hybrid and consortium architectures blend elements of both.

The four types of blockchain networks

1. Public blockchains

Definition and governance

A public blockchain is an open, decentralised network that anyone can join to validate transactions and create new blocks. Visa describes public blockchains, also known as trustless blockchains, as being analogous to a city’s public transport system: anyone can buy a ticket and travel; likewise, anyone can participate in the network. Paxos notes that public blockchains are 'the town squares of the blockchain world' - decentralised and open to all participants, they are designed for robust participation. They rely on incentive-driven consensus mechanisms (proof-of-work, proof-of-stake or similar) to ensure honest behaviour among anonymous participants.

Governance in public chains is typically informal and distributed. Protocol changes often require broad community agreement and may involve contentious voting or hard forks. The network’s cryptocurrency usually funds development and secures the chain.

Pros and cons

Advantages:

- Decentralization and censorship resistance. With no single authority controlling the ledger, public networks resist censorship or unilateral changes. Anyone can verify the state of the ledger.

- Transparency and auditability. Every transaction is publicly visible, enabling independent verification and easy auditing.

- Network effects and security. Permissionless participation encourages a large number of nodes, making the network more resilient and reducing the risk of 51 % attacks.

Drawbacks:

- Limited throughput and high energy use. Proof‑of‑Work networks like Bitcoin are energy‑intensive and process relatively few transactions per second.

- Public data exposure. Sensitive business data cannot be kept private on a fully public chain.

- Volatile governance. Protocol upgrades can be slow and sometimes contentious due to lack of centralized authority.

Best use cases

Public blockchains excel where trust minimization and openness outweigh privacy concerns. Typical applications include:

- Cryptocurrencies and digital assets. Bitcoin, Ethereum and other open networks enable borderless payments and decentralized finance.

- Tokenized fundraising and NFTs. Public networks support token issuance for crowdfunding and non‑fungible tokens.

- Open protocols. Decentralized applications (dApps), smart contracts and protocols for decentralized identity or data storage rely on public chains for trustless execution.

Examples

- Bitcoin (BTC). The original blockchain uses proof‑of‑work to secure a completely open network.

- Ethereum (ETH). Ethereum introduced general‑purpose smart contracts and currently uses proof‑of‑stake.

- Solana and Cardano. Other public chains optimize for higher throughput or alternative consensus mechanisms.

2. Private blockchains

Definition and governance

A private blockchain is a closed network controlled by a single organization or a designated owner. Visa describes a private blockchain as a “closed, participant‑restricted network” in which only authorized entities may participate, validate transactions and generate blocks. Participation requires identification and approval, and access policies can restrict both reading and writing to the ledger. Paxos notes that private blockchains restrict participation to select members and are often controlled by a single entity. Governance is centralized: the owning organization defines rules, executes upgrades and controls node membership.

Pros and cons

Advantages:

- Privacy and confidentiality. Only authorized participants can view or submit transactions, enabling compliance with data‑protection regulations and protection of proprietary information.

- High performance. Because the number of nodes is limited and participants are known, consensus algorithms can be optimized for high throughput and low latency.

- Control and compliance. Companies can tailor governance and transaction rules to regulatory needs. Centralized control makes software updates and policy changes straightforward.

Drawbacks:

- Centralization risks. Trust must shift from a distributed network to the controlling entity. Misbehavior by the owner can undermine the ledger’s integrity.

- Limited decentralization. The closed nature reduces resilience; a failure of the central authority or collusion among permitted nodes can disrupt the network.

- Interoperability challenges. Private chains may lack compatibility with other networks, making asset transfers and integration more complex.

Best use cases

Private blockchains suit scenarios where a single organization needs a tamper‑resistant ledger but must restrict access. Examples include:

- Internal record‑keeping. Enterprises can use private chains for supply‑chain tracking, asset management or audit trails, ensuring traceability without exposing data publicly.

- Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). Many CBDC prototypes are built on private ledgers to control issuance and enforce monetary policy while leveraging blockchain’s efficiency.

- Enterprise resource management. Corporations may deploy private blockchains for payroll, procurement or compliance reporting, integrating smart contracts to automate rules.

Examples

- Hyperledger Fabric and Besu. These frameworks provide modular, permissioned networks controlled by a single organization but can support consortium models.

- Quorum and Corda Enterprise. Private variants of Ethereum and Corda tailored for enterprise use.

3. Consortium blockchains

Definition and governance

A consortium or federated blockchain is a permissioned network governed by a group of pre‑selected organizations rather than a single entity. Visa explains that consortium blockchains are administered by multiple organizations, often representing public and private entities, which jointly control the network. CFTE notes that a consortium blockchain is governed by multiple organizations; it is permissioned but partially decentralized because decision‑making power lies with several members.

Governance rules - including consensus mechanisms, membership criteria and upgrade processes - are negotiated among consortium members. The goal is to share control while ensuring efficiency and privacy for the participating entities.

Pros and cons

Advantages:

- Shared trust and cost. Multiple organizations share operational responsibilities and costs, increasing resilience compared with a single private chain.

- Selective transparency and privacy. Consortium members decide who can read or write data and can protect sensitive business information while sharing what is necessary across the consortium.

- Higher throughput than public chains. Known participants and lighter consensus protocols enable faster transactions. CFTE emphasizes that transaction speed is high because few nodes participate in consensus.

Drawbacks:

- Coordination complexity. Establishing and governing a consortium requires agreement among multiple organizations. CFTE points out that launching a consortium is tedious and requires cooperation, which can lead to disputes or slow upgrades.

- Partial decentralization. While more decentralized than a private chain, a consortium still relies on a closed set of actors, creating potential for collusion or unequal influence.

- Governance inertia. Protocol changes require collective agreement, which may slow innovation.

Best use cases

Consortium blockchains are ideal when several parties in a sector need to collaborate but do not trust one entity to control the ledger. Suitable scenarios include:

- Supply chain and logistics. Manufacturers, suppliers, logistics providers and retailers jointly maintain a shared ledger to track goods, certifications and provenance. The closed membership protects proprietary data while enabling end‑to‑end visibility.

- Trade finance and interbank settlements. Banks and financial institutions form consortia to streamline letters of credit, cross‑border payments and settlements. Examples include the Marco Polo Network and the Energy Web Foundation.

- Healthcare and insurance data exchange. Hospitals and insurers share claims data on a consortium chain to reduce fraud and accelerate reimbursements.

Examples

- R3 Corda. A distributed ledger platform designed for regulated industries; it supports consortia where participants negotiate direct transactions and share governance.

- Hyperledger Fabric consortia. IBM and Walmart use Fabric for food traceability, with multiple suppliers and retailers participating.

- Marco Polo Network. An international consortium facilitating trade finance among banks and corporations.

4. Hybrid blockchains

Definition and governance

Hybrid blockchains blend elements of permissionless and permissioned networks. Visa describes hybrid (or semi‑private) blockchains as allowing members to decide which transactions are public and who can participate; they strike a balance between security, privacy and openness. Enterprise Networking Planet notes that hybrid networks have one central authority but open some nodes for public validation, adding transparency without relinquishing control. Paxos adds that hybrid blockchains offer selective transparency, customizable levels of access and a balance between decentralization and control.

In hybrid systems, a portion of the ledger or certain transactions may be visible on a public chain, while sensitive data resides on a permissioned layer. Governance may involve an owner or consortium controlling the private component and using the public component to anchor proofs or enable public auditability.

Pros and cons

Advantages:

- Privacy with public verifiability. Sensitive business logic and data stay on a private layer, while cryptographic proofs or selected transactions are posted publicly. This allows auditors or partners to verify integrity without accessing raw data.

- Flexibility. Organizations can configure what to expose and to whom, balancing compliance, confidentiality and transparency.

- Improved performance. Most transactions can be processed on the private layer, reducing the load on public networks and enabling higher throughput.

Drawbacks:

- Complex architecture. Managing two layers increases technical complexity and demands careful governance. Paxos warns that the dual aspects can be resource‑intensive and require elaborate protocols.

- Potential points of failure. Connecting a private chain to a public chain introduces integration risks and requires robust security design.

- Governance challenges. Deciding which data is public and which remains private requires consensus among participants and may be contentious.

Best use cases

Hybrid blockchains are suited to use cases where some data must be publicly verifiable while other data must remain confidential. For example:

- Asset tokenization with regulatory compliance. Financial institutions may record trades privately but publish hashed proofs or summary data on a public chain to provide auditability.

- Healthcare records. Hospitals could maintain patient data privately while sharing anonymized proofs with insurers or regulators.

- Voting systems. A hybrid chain could allow citizens to cast votes privately while posting anonymized tallies on a public ledger to ensure transparency.

Examples

- XinFin (XDC Network). A hybrid blockchain that uses a permissioned layer for enterprise use and a public consensus layer for cross‑border settlement.

- IBM Blockchain Platform on Hyperledger Fabric. IBM supports hybrid deployments where private channels handle confidential data and anchor hashes are periodically written to public chains for auditability.

- Dragonchain. Initially developed at Disney, Dragonchain uses a hybrid architecture to allow business logic on private nodes while leveraging public chains for proof of existence.

Comparison table

The following table summarizes key differences among the four blockchain types. Values are indicative rather than absolute and may vary by implementation.

| Type | Access (permission model) | Governance | Pros | Cons | Typical use cases |

| Public | Open participation; anyone can validate and submit transactions (permissionless by default) | Decentralized community; changes require broad consensus | High decentralization and transparency; strong security through network effect | Low throughput; energy‑intensive; public data exposure | Cryptocurrencies, dApps, tokenized assets |

| Private | Restricted to a single organization and its approved nodes (permissioned) | Centralized control by one entity | High performance and privacy; easy to enforce compliance | Single point of failure; limited decentralization | Internal business processes, enterprise record keeping, CBDCs |

| Consortium | Restricted to a set of organizations (permissioned) | Shared governance by consortium members | Shared trust; selective transparency; faster than public networks | Coordination complexity; potential for collusion | Supply chain, trade finance, inter‑bank settlement, healthcare data exchange |

| Hybrid | Mix of permissionless and permissioned layers; selective participation | Hybrid governance: owner or consortium controls private component, public layer provides auditability | Privacy with public verifiability; flexibility; improved performance | Complex architecture; integration risks; governance challenges | Regulated asset tokenization, healthcare records, voting systems |

Choosing the right type: decision framework

Selecting a blockchain architecture requires considering technical, regulatory and business factors. The following framework can guide your decision:

- Define objectives and requirements. Identify the primary problem you’re solving (e.g., multi‑party trust, process automation, transparency). List regulatory obligations, privacy needs and performance targets.

- Determine trust assumptions. Who are the participants? Do they trust each other? Are they competitors? High trust and small participant sets may point toward a private or consortium chain. No trust and public verification requirements favor a public or hybrid chain.

- Assess data sensitivity. Determine whether data must remain confidential. If so, avoid fully public networks unless encryption or zero‑knowledge proofs can maintain privacy. Hybrid and private chains allow granular control of data access.

- Evaluate scalability and performance. Public networks are slower and more expensive to operate. If your application requires high throughput, consider permissioned or hybrid models.

- Consider governance and maintenance. Decide who will manage node membership, consensus upgrades and protocol changes. Consortium and hybrid chains require clear governance frameworks among participants.

- Plan for interoperability. Future integration with other chains or systems may influence your choice. Public and hybrid networks may provide easier interoperability, whereas private chains may require bridges and additional infrastructure.

Common mistakes and myths

Understanding blockchain architectures helps avoid costly missteps. Here are common misconceptions:

- Myth: “Blockchain must be public to be decentralized.” Decentralization is a spectrum. Consortium and hybrid networks achieve partial decentralization by spreading control among multiple parties.

- Myth: “Permissioned blockchains aren’t secure.” Permissioned chains still use cryptographic techniques and consensus protocols. NIST notes that permissioned networks maintain traceability, resilience and redundancy akin to permissionless chains, but with faster consensus due to known participants.

- Mistake: Ignoring governance. Even technically sound networks fail when governance is unclear. Define roles, decision‑making processes and dispute‑resolution mechanisms early, especially in consortia.

- Mistake: Over‑engineering privacy. Public blockchains can support privacy through advanced cryptography; however, unnecessary complexity can introduce vulnerabilities. Evaluate whether simpler permissioned approaches suffice.

- Myth: “Hybrid blockchains eliminate compliance risk.” Hybrid architectures still require careful design to meet data‑protection regulations. They can complicate compliance if roles and data flows are not well defined.

Mini case examples

Case 1: Food supply chain traceability

Scenario: A global retailer wants to track produce from farm to shelf to quickly identify contamination sources. Multiple farmers, processors, distributors and retailers must share data.

Solution: The retailer and its suppliers form a consortium blockchain using Hyperledger Fabric. Each participant runs a node and records shipment data (harvest dates, lot numbers, storage conditions). Smart contracts enforce data formats and time‑stamps. Only consortium members can write data, but regulators receive read access. When a recall occurs, the ledger pinpoints affected batches within minutes.

Why it works: The consortium model balances privacy and collaboration. Participants trust the network because governance is shared. The permissioned design ensures sensitive supply chain data remains confidential while regulators and auditors have transparency.

Case 2: Cross‑border payments platform

Scenario: A fintech startup wants to enable low‑cost cross‑border transfers for SMEs. The platform must facilitate trust among unknown counterparties and operate across jurisdictions.

Solution: The company builds on a public blockchain like Stellar or Ethereum, leveraging its global access and robust security. A smart contract governs escrow and settlement. Users hold digital tokens representing fiat currency. To address compliance, the startup partners with regulated custodians who handle KYC/AML off‑chain.

Why it works: A public chain offers censorship resistance and global liquidity, critical for cross‑border payments. Off‑chain compliance ensures regulatory obligations are met without compromising openness. The transparent ledger instils confidence in users.

Case 3: Private equity fund management

Scenario: An investment firm wants to digitize fund shares, automate capital calls and simplify audits while keeping investor data confidential.

Solution: The firm deploys a private blockchain using Quorum. Only the general partner and approved limited partners operate nodes. Smart contracts automate capital calls and distributions. Audit firms receive read‑only access to verify transactions. All investor identities and balances remain confidential within the permissioned network.

Why it works: A private chain provides the confidentiality and performance needed for sensitive financial data. Centralized governance allows quick upgrades and regulatory compliance.

Case 4: Digital identity for healthcare

Scenario: Patients need to carry portable medical histories while allowing different providers to access relevant data securely.

Solution: A national health consortium deploys a hybrid blockchain. Patient identifiers and medical records are stored on a permissioned network controlled by healthcare providers. Hashes of records and cryptographic proofs are anchored on a public chain (e.g., Ethereum) so that regulators and insurers can verify authenticity without viewing personal data. Patients manage access via self‑sovereign identity wallets.

Why it works: The hybrid model provides privacy for sensitive health data while ensuring public verifiability. Anchor hashes on a public chain deter tampering and enable patients to prove the integrity of their records to external parties.

FAQ

1. What is the difference between a blockchain’s type and its permission model?

The type - public, private, consortium or hybrid - describes who operates and governs the network. The permission model describes who can publish blocks or view data. For example, a private chain is typically permissioned, but a hybrid chain combines permissioned and permissionless elements. Choosing a type involves assessing governance, trust and performance requirements.

2. Are public blockchains always permissionless?

Most public networks are permissionless by design, but some projects experiment with public-but-permissioned models where anyone can view data yet publishing blocks requires permission. These are less common and may sacrifice decentralization.

3. Do private blockchains still use consensus mechanisms?

Yes. Even though participants are authorized, they must agree on the ledger’s state. Permissioned networks often use consensus algorithms like Proof‑of‑Authority or Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance, which are faster and less resource‑intensive than Proof‑of‑Work.

4. How secure are consortium blockchains compared with public ones?

Security in consortium chains comes from the reputational and legal accountability of the members rather than pure computational work. While they lack the vast decentralization of public chains, consortium chains can still be secure if members are vetted and consensus rules are strict. However, fewer nodes mean potential vulnerabilities if members collude or misconfigure security.

5. When should I choose a hybrid blockchain?

Choose hybrid architectures when you need both confidentiality and public verifiability. Examples include regulated financial products, supply chains requiring public proofs of provenance, or identity systems that must maintain privacy while providing audit trails. Be prepared to manage additional complexity and governance.

6. Can blockchains be integrated with existing systems?

Yes. Most enterprise blockchains provide APIs and software development kits for integration. When designing integration, consider data formats, privacy requirements and transaction finality. Interoperability standards are still evolving; using widely adopted platforms like Hyperledger or Ethereum can ease future integration.

7. Are blockchains always the right solution?

No. Blockchain introduces overhead and complexity. If a trusted central database can address your use case efficiently, blockchain may not be necessary. Evaluate whether decentralization, immutability and shared control provide clear benefits for your application.

Conclusion and call to action

The blockchain landscape has matured significantly since the launch of Bitcoin. Today’s networks fall into four broad categories: public, private, consortium and hybrid. Each category has its own distinct governance model, strengths and trade-offs. It is essential for founders, product managers and CTOs contemplating blockchain solutions to understand these types and how they map to permissioned and permissionless architectures.

Public blockchains offer maximum openness and decentralisation, but present challenges in terms of performance and privacy. Private chains deliver control and speed, but centralise trust. Consortium networks strike a balance for industry collaborations, and hybrid architectures can combine the best of both worlds with careful design and governance.

Selecting the right type begins with clearly articulating business goals, trust assumptions, data sensitivity and regulatory requirements. Use the decision-making framework in this article to determine the most suitable architecture for your needs. Avoid common misconceptions and learn from case studies that demonstrate how organisations are utilising different models for supply chains, finance, private equity and digital identity. With informed choices and robust governance, blockchains can deliver tangible value beyond the hype.

Are you ready to explore which blockchain model fits your product? Assess your requirements, consult with stakeholders, and start prototyping. Understanding the nuances of the four types of blockchain software solutions will help you to build secure, scalable solutions that are aligned with your strategic goals.

Leave a Comment